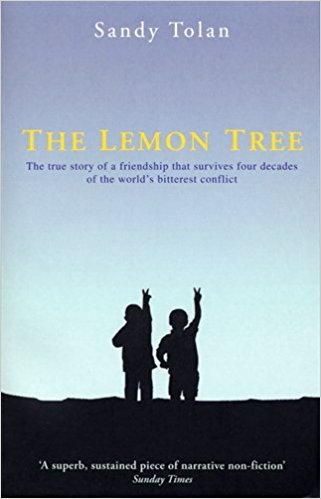

Sandy Tolan’s (2008) “The Lemon Tree: The True story of a friendship that survives four decades of the world’s bitterest conflict” is an excellent read for anyone who seeks to understand the Middle East conflict better but who does not want to get caught up in the competing narratives about it. Rather than giving a one-sided account or being overtly analytical, Tolan offers the non-fiction narrative of two unlikely friends. Bashir, a Palestinian Arab, whose peaceful life ends at the age of six when his family is misplaced from their native village Ramla in Palestine, and Dalia, the daughter of Bulgarian Jews who became settlers in the house which Bashir was forced to leave behind. The book gets its title from the lemon tree in the house’s court yard which Bashir’s father planted and which Dalia’s family cherished.

Sandy Tolan’s (2008) “The Lemon Tree: The True story of a friendship that survives four decades of the world’s bitterest conflict” is an excellent read for anyone who seeks to understand the Middle East conflict better but who does not want to get caught up in the competing narratives about it. Rather than giving a one-sided account or being overtly analytical, Tolan offers the non-fiction narrative of two unlikely friends. Bashir, a Palestinian Arab, whose peaceful life ends at the age of six when his family is misplaced from their native village Ramla in Palestine, and Dalia, the daughter of Bulgarian Jews who became settlers in the house which Bashir was forced to leave behind. The book gets its title from the lemon tree in the house’s court yard which Bashir’s father planted and which Dalia’s family cherished.

The story begins in 1967. The six-day war is just over and for the first time it is possible for Palestinian Arabs to travel to the lands which they had left in the war of 1948. Bashir, a young man in his mid-twenties, takes his chance to visit his native village Ramla with his cousins and eventually ends up ringing the doorbell of his birth place. There he meets young Dalia, who is at home over the summer from her studies and her training in the Israeli army. To Bashir’s surprise Dalia is welcoming him and his cousins and invites them in. The beginning of an unlikely friendship.

Tolan skilfully combines facts about the Middle East conflict with telling the individual stories of Bashir and Dalia. Dalia starts early to doubt the narrative that the Arabs have fled their villages cowardly in 1948 simply leaving everything they owned and built behind but she is torn between acknowledging the rights of the native Arab population and her own attachment to the state of Israel. Bashir spends his life struggling for his dream of returning home and being repeatedly imprisoned for alleged links to the violent arms of the Arab resistance. Their lives take very different courses and they disagree on politics, yet Bashir and Dalia meet repeatedly over the years. The house they both call home is eventually converted into a centre for Arab and Jewish youth in Ramla. Through the story of Bashir and Dalia, Tolan covers the history of the Middle East conflict from the early stages of Zionism, the Balfour declaration in 1917, the wars between Israel and Arab nations, the failed peace process in the 1990s, up to the situation today.

What makes Tolan’s book a worthwhile read is that he offers personal views on the conflict, which to me have shed new light on it. For example, I was aware that many of the early Jewish migrants who came to Israel soon after 1948 were Holocaust survivors with a strong desire for security and a place to call home. However, I did not realise that for many migration meant to give up citizens’ rights in their country of origin. For them, coming to Israel was a move which could not be reverted later. Subsequently, the demand from radical Arabs to reclaim Palestine and to expel all settlers who came after 1917 was unacceptable to the people of Israel even if they recognised the Arab struggles. The clash of two nations over their sense of belonging to Palestine and their desire to exercise their rights to a peaceful home strikes me as complicated and sad. Both sides build their views on personal experience of injustice, with the only difference that the the Palestinian Arabs experience injustice today while the Jewish population in Israel carries a memory of unspeakable injustice in the past.

The book ends with the death of the Lemon Tree in 1998. Dalia decides to wait for Bashir’s family to return to decide what to do about it but eventually, in 2005, some of the teenagers at the youth centre spontaneously decide to plant a new tree. Dalia realises that moving on and putting hope into the hands of the next generation is the right thing to do and helps them. When Bashir learns about it later, he is pleased and hopes he will one day see the new tree for himself.